Over the last 17 years, I have grown and trialed thousands of different foliage, filler, vegetable, fruit, and flower varieties in search of the best ones for cutting. If it has any potential as a cut flower, I’ve probably grown it!

Through this process, I discovered that there was a huge disconnect between what florists and designers wanted and what local farmers were able to grow. While there are many beautiful new flower varieties coming onto the market each year, nearly all of them have been bred with large-scale production and global transportation in mind.

This is because most of the cut flowers that you see in stores and in wedding designs are grown on massive farms near the equator, sprayed with many types of chemicals, and once harvested, spend days if not weeks in a box out of water traveling to every corner of the world.

I have talked with so many huge seed companies, brokers, and plant dealers over the years, sharing my insights about the industry and encouraging them to invest more energy into breeding varieties for the local market because the seasonal flower movement needs their support.

I have talked with so many huge seed companies, brokers, and plant dealers over the years, sharing my insights about the industry and encouraging them to invest more energy into breeding varieties for the local market because the seasonal flower movement needs their support.

Those meetings and visits were always cordial, but they never really amounted to anything. After years of begging the big corporations to take action, I started to ask the question, is there any way I could figure out how to do this myself?

While the path forward was not very clear, I was convinced that there must be a way to help solve some of the big problems in the floral industry at the ground level.

While the path forward was not very clear, I was convinced that there must be a way to help solve some of the big problems in the floral industry at the ground level.

I would say the hardest part about this journey so far has been how little information there is available on the subject. Having to learn everything from scratch through years of trial and error has been quite challenging.

Even if you could have access to all the resources in the world, breeding new plant varieties is still a slow, complex, and oftentimes discouraging process that spans many, many years and while it’s been one of the most challenging things I’ve ever taken on, I have learned so much along the way, both about plants and nature.

Even if you could have access to all the resources in the world, breeding new plant varieties is still a slow, complex, and oftentimes discouraging process that spans many, many years and while it’s been one of the most challenging things I’ve ever taken on, I have learned so much along the way, both about plants and nature.

In an effort to make more information about this topic available, we’ve spent the last year carefully documenting all of the processes around seed saving and what we understand so far when it comes to flower breeding. My hope is that this project will eventually become a book, or possibly a course in the future.

One of the most important lessons that I learned early on, is that if you don’t have a really clear set of goals when it comes to breeding, you’ll never get anywhere. Every day there are so many beautiful, interesting, and unusual flowers that emerge in the field and it can be really easy to want to keep them all. If you don’t have a clear set of criteria to measure new discoveries against, things can quickly get out of control.

One of the most important lessons that I learned early on, is that if you don’t have a really clear set of goals when it comes to breeding, you’ll never get anywhere. Every day there are so many beautiful, interesting, and unusual flowers that emerge in the field and it can be really easy to want to keep them all. If you don’t have a clear set of criteria to measure new discoveries against, things can quickly get out of control.

If I kept every variety that showed any amount of promise each year, it would be impossible to grow and care for them all, so I try and be as selective as possible which sometimes feels impossible!

When breeding new flower varieties, I’m always measuring against a set of strict criteria. They must have beautiful coloring and a unique form that will lend itself to flower arranging. Long stem length is a must. I want them to thrive in a wide range of climates (especially those that are hot or humid), and be both vigorous and healthy so that even beginning gardeners will have success with them.

When breeding new flower varieties, I’m always measuring against a set of strict criteria. They must have beautiful coloring and a unique form that will lend itself to flower arranging. Long stem length is a must. I want them to thrive in a wide range of climates (especially those that are hot or humid), and be both vigorous and healthy so that even beginning gardeners will have success with them.

To ensure that local growers have the advantage over imported blooms, I am focusing on breeding flowers that don’t ship well so if floral designers or wholesale flower sellers want to get their hands on them, they will have to buy locally.

There are three main groups of plants that I’ve been focusing my breeding efforts on, the first being zinnias.

There are three main groups of plants that I’ve been focusing my breeding efforts on, the first being zinnias.

These flowers have so many wonderful qualities, including being heat tolerant, easy to grow, quite resistant to pests, and an incredibly productive cut flower—the more you pick them, the more they bloom.

And anyone, no matter their skill level, can have success growing them.

But for many years nearly all of the zinnias on the market have been bright, bold primary colors, and while beautiful, there is a huge lack of softer, more feminine colors available. Back in 2016, I started working on my very first zinnia variety, a soft palomino-colored beauty I named Golden Hour (pictured below).

But for many years nearly all of the zinnias on the market have been bright, bold primary colors, and while beautiful, there is a huge lack of softer, more feminine colors available. Back in 2016, I started working on my very first zinnia variety, a soft palomino-colored beauty I named Golden Hour (pictured below).

In the years since, so many incredible varieties have emerged and this year I have more than 100 unique zinnias in the works here on the farm ranging from large, tufted beauties to miniature, marble-sized blooms (that look like little macaroons) to densely packed domes in a range of pastel shades to tiny cactus types and everything in between.

In the years since, so many incredible varieties have emerged and this year I have more than 100 unique zinnias in the works here on the farm ranging from large, tufted beauties to miniature, marble-sized blooms (that look like little macaroons) to densely packed domes in a range of pastel shades to tiny cactus types and everything in between.

What they all have in common is unique coloring, beautiful flower forms, and long, strong stems, making them ideal for cutting.

The second group of plants I’m working on are celosia. They are vigorous, free-flowering, easy to grow, and love the heat. But the best part are their fuzzy, velvet-like flowers that come in a distinct range of shapes, including fans, plumes, and brains.

The second group of plants I’m working on are celosia. They are vigorous, free-flowering, easy to grow, and love the heat. But the best part are their fuzzy, velvet-like flowers that come in a distinct range of shapes, including fans, plumes, and brains.

While they have so many wonderful qualities, there are very few varieties on the market that have more soft, subtle coloring.

Over the years I have learned how to isolate the softer colors I love including shades of blush, dusty rose, champagne, peach, and icy lime. This season I’m working on about two dozen new varieties, plus continuing to improve some of the mixes we currently offer.

Over the years I have learned how to isolate the softer colors I love including shades of blush, dusty rose, champagne, peach, and icy lime. This season I’m working on about two dozen new varieties, plus continuing to improve some of the mixes we currently offer.

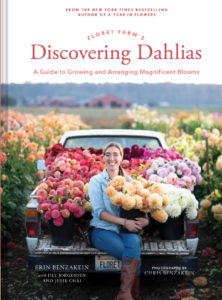

By far the largest group of plants in the breeding program are the dahlias, and while I have a complicated relationship with these flowers, I just can’t seem to give them up!

By far the largest group of plants in the breeding program are the dahlias, and while I have a complicated relationship with these flowers, I just can’t seem to give them up!

They have so many wonderful qualities, including being easy to grow, unmatched in terms of production, and coming in so many shapes, sizes, and colors—plus they multiply each growing season.

Over the last few years, as I’ve gotten deeper into the process of breeding, I’ve found that I’m most drawn to the novelty varieties, including collarettes, anemones, and single flowers with an open center. These types seem to be the most attractive to pollinators and add such magical quality to flower arrangements.

Over the last few years, as I’ve gotten deeper into the process of breeding, I’ve found that I’m most drawn to the novelty varieties, including collarettes, anemones, and single flowers with an open center. These types seem to be the most attractive to pollinators and add such magical quality to flower arrangements.

When it comes to breeding open-centered varieties, one of the more challenging things is that many don’t hold onto their petals very well after being picked. Finding varieties in these forms that are both beautiful and long lasting has become my mission.

This season, we’ll be growing nearly 200 breeding varieties and really putting them through the paces to ensure that each one meets my strict criteria. I’m excited to see how they perform and continue to refine this beautiful line.

This season, we’ll be growing nearly 200 breeding varieties and really putting them through the paces to ensure that each one meets my strict criteria. I’m excited to see how they perform and continue to refine this beautiful line.

If you want to learn more about the dahlia breeding project, be sure to read this blog post.

Last season I had such high hopes of having enough of some of these treasures to share with the world. But we experienced the coldest, wettest spring on record and lost more than 50 percent of our plants before the season even started. The losses were devastating.

Last season I had such high hopes of having enough of some of these treasures to share with the world. But we experienced the coldest, wettest spring on record and lost more than 50 percent of our plants before the season even started. The losses were devastating.

Our poor stressed plants struggled throughout the growing season but thankfully by autumn, we were able to collect enough seed to continue on. A gift I don’t take for granted.

Despite the setbacks, we are forging ahead and have built a new little fleet of hoops to help give plants more protection from weather extremes. So far this spring is off to a great start and I’m thrilled to see all of my plant friends returning for another season.

Despite the setbacks, we are forging ahead and have built a new little fleet of hoops to help give plants more protection from weather extremes. So far this spring is off to a great start and I’m thrilled to see all of my plant friends returning for another season.

My hope is that the work we’re doing here will eventually make its way out into the world and help open up a whole new world of possibility for the seasonal flower movement.

My hope is that the work we’re doing here will eventually make its way out into the world and help open up a whole new world of possibility for the seasonal flower movement.

If you’d like to receive progress updates about the Floret Originals, you can join the waitlist below.

Please note: If your comment doesn’t show up right away, sit tight; we have a spam filter that requires us to approve comments before they are published.

Amy L on

It is wonderful what you are doing! I think it is important that more of the flowers are grown locally and less over seas. I would love to be a test garden for this project. In upstate NY, we get a lot more rain than your area. I would be willing to grow only say the pink celosia and no other or do a side by side comparison for your study. I have a few acres I could donate to this project!